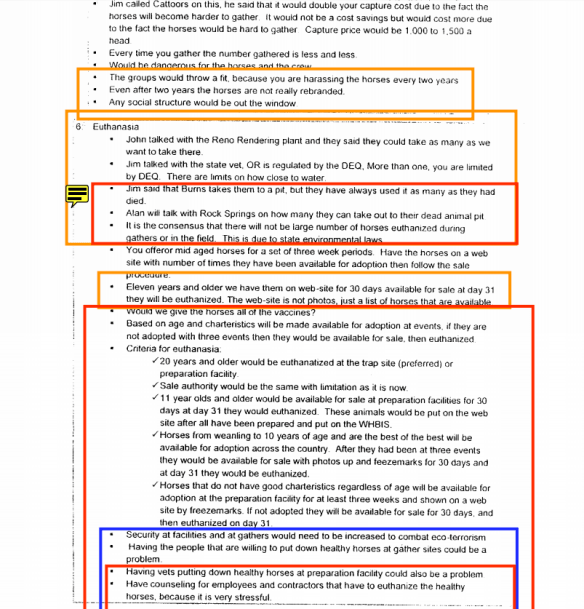

Truck in the pens (© Anne Novak, All rights reserved)

When Velma Johnston almost single-handedly persuaded Congress to pass the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, her goal was to protect an icon of the American West that had been slaughtered, poisoned and abused and was quickly disappearing.More than four decades later, the woman known as “Wild Horse Annie” would undoubtedly be shocked by what her law has wrought: so many mustangs, stashed in so many places, that authorities admit they have no idea how to handle them all.

Under the law, the federal government is responsible for more than 40,000 mustangs on the range in 10 Western states, where they compete with cattle and wildlife for increasingly scarce water and forage. The public desire to adopt them is limited. Contraceptive efforts have largely failed. U.S. law — reaffirmed this month — effectively precludes slaughtering them, or selling them to anyone who would. Activists want the horses left on the land.

Solving the decades-old problem is the task of the federal Bureau of Land Management. Already it manages 50,000 horses and burros it has rounded up and sent to pastures and corrals. But it is rapidly running out of places for more.

Now, by devoting about $1.5 million from the new budget agreement for fiscal 2014, the agency is ready to take another shot at one of the West’s most intractable wildlife problems. It is inviting anyone with a legitimate idea of how to curb the horse and burro populations to step up and propose it. The agency will study the ones it finds most promising and try again to find a solution.

“We need all the help we can get,” said Ed Roberson, the BLM’s assistant director of resources and planning.

The agency periodically takes wild horses from 179 “herd management areas” it controls on 31.6 million acres, mostly when they threaten to overwhelm the available food and water or destroy the surroundings, officials said. It sends them to private pastures if space is available and holds the rest in corrals.

Not only do these efforts feature the unfortunate visual of panicked mustangs fleeing low-flying helicopters, but activists and others have claimed that horses have been injured and treated inhumanely during roundups.

“We don’t have an overpopulation problem,” said Anne Novak, executive director of Protect Mustangs, a horse advocacy group. “The only overpopulation problem is in the holding pens.”

The BLM says that the open range it manages can support 26,677 horses and burros, and estimates that 40,605 are roaming that land. A National Research Council study released in June concluded that the agency may have undercounted by 10 to 50 percent, and that horse populations were probably growing at 15 to 20 percent every year.

The mustangs, offspring of horses left behind by miners, ranchers, Native Americans and others, have no natural predators, except for an occasional mountain lion or bear. Left alone on the range, the agency predicts, their population would soar to 145,000 by 2020.

Meanwhile, the BLM is sheltering and feeding 33,608 horses in pastures at $1.30 per head each day, and 16,160 horses and burros in “short-term corrals” at four times the expense, officials said. (The temporary stays can last as long as 18 months.)

Joan Guilfoyle, chief of the BLM’s wild horse and burro division, predicted that the holding areas in states such as Kansas and Oklahoma will chew up 64 percent of the $77 million Congress gave the program for fiscal 2014.

“Our long-term goal is to reduce that,” she said. “We don’t consider that a success story. We haven’t had very many options.”

Bruce Wagman, a California-based attorney who represents numerous animal protection groups across the country, argued that the government’s approach violates the spirit of the 1971 law.

“They’ve been doing the wrong thing since day one,” he said. “Instead of protecting and preserving them, they are doing the opposite.”

The Nevada Association of Counties and the Nevada Farm Bureau Federation couldn’t disagree more. Last month, they sued the BLM, alleging that it is not enforcing the portion of the 1971 law that requires it to manage wild horses in a way that maintains ecological balance for all species, including the millions of cattle that graze on federal land.

“They’re not managing the herds,” said Lorinda Wichman, a Nye County, Nev., commissioner and president-elect of the state’s Association of Counties. “We have some herds in Nye County that are 600 percent over” what the area can support.

More than half the wild horses are in Nevada. The overcrowding, coupled with the drought plaguing the Southwest, has “severe impacts on the rangeland. It has severe impacts on the natural riparian areas. And in the long run, it has severe impacts on the horses themselves,” said Zach Allen, director of communications for the Nevada Farm Bureau.

Novak, of Protect Mustangs, dismissed the notion that wild horses have destroyed grazing lands that ranchers need to feed their cattle. She cited work by Princeton University researchers that shows that allowing wild animals to graze alongside cattle can actually result in healthier cows. Their conclusions were based on studies conducted in Kenya, where cattle paired with donkeys gained 60 percent more weight than those left to graze only with other cows. The researchers said that the donkeys ate the upper portion of grass that cows have difficulty digesting, leaving behind lush lower vegetation on which cattle thrive.

One obvious solution, sending the horses to slaughter, is out of the question. The BLM does not knowingly auction horses to anyone who would slaughter them. And the last of several domestic horse-slaughtering plants ceased operation in 2007 after Congress withheld funding for federal inspectors.

When that funding was restored in 2011, several companies sought permits from the Department of Agriculture to resume horse-slaughtering operations. The most high-profile was Valley Meat in New Mexico, whose efforts triggered renewed debate — and many months of legal fights — over whether the practice should be allowed.

When Congress cut the funding for inspectors, “it did far more to hurt the welfare of horses,” said A. Blair Dunn, an attorney who has represented Valley Meat. “People were just abandoning them. . . . They are starving to death or dying of thirst.”

Wagman, the attorney who represents horse advocacy groups, responded that “horse slaughter is inherently inhumane. Even if it’s not a legal issue, it’s an ethical issue.”

The argument became moot recently when Congress passed a budget that again withholds money for inspectors in horse-

slaughter plants.

Adoption was once a serious option. In fiscal 1995, 9,655 horses and burros were adopted, according to the BLM, but that dropped to a low of 2,583 by fiscal 2012, for reasons that aren’t clear.

That leaves fertility control as the most promising alternative. One drug, porcine zona pellucida, is effective for a year and can be injected into horses on the range. But longer-acting versions have proven to be not nearly as reliable, Guilfoyle said.

Until a new idea comes along — the BLM hopes its $1.5 million offer will generate creative suggestions — the agency is left with a combination of fertility control and roundups.

“What is the solution? You know, I really wish I knew,” said Wichman, the county commissioner. “As a race, I believe we have loved our pets and our animals into a corner, because as soon as we started playing Mother Nature, we kind of messed with the balance of things.”

Please comment here.

Cross posted from the Washington Post for educational purposes: http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/us-looking-for-ideas-to-help-manage-wild-horse-overpopulation/2014/01/26/8cae7c96-84f2-11e3-9dd4-e7278db80d86_story.html

The Devil’s Garden lies directly under the Pacific Flyway. During their migration from Alaska and Canada to Mexico, hundreds of thousands of waterfowl use the wetlands as rest stops. Several of the reservoirs on the district are stocked by the California Dept of Fish and Game with bass or trout. The Garden is also shared by Rocky Mountain elk, pronghorn antelope, sage grouse, turkeys, coyotes and wild horses.

The Devil’s Garden lies directly under the Pacific Flyway. During their migration from Alaska and Canada to Mexico, hundreds of thousands of waterfowl use the wetlands as rest stops. Several of the reservoirs on the district are stocked by the California Dept of Fish and Game with bass or trout. The Garden is also shared by Rocky Mountain elk, pronghorn antelope, sage grouse, turkeys, coyotes and wild horses.